Since today is the feast day for St. Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin and we are preparing to celebrate the Virgin of Guadalupe Day on Sunday, I found myself thinking of the story that started it all:

On an early December morning in 1531, an Aztec peasant named Juan Diego was making his way along the path of Tepayec Hill on the outskirts of Mexico City. He was on his way to Mass. As he walked along, he began to hear beautiful music, and then he saw a beautiful, radiant lady. She called him by name, in the familiar, as if he were her beloved child: “Juanito, Juan Dieguito.” As he approached her, she said:

Know for certain, least of my sons, that I am the perfect and perpetual Virgin Mary, Mother of Jesus, the true God, through whom everything lives, the Lord of all things near and far, the Master of Heaven and earth. It is my earnest wish that a temple be built here to my honor. Here I will demonstrate; I will manifest; I will give all my love, my compassion, my help and my protection to the people. I am your merciful mother, the merciful mother of all of you who live united in this land, and of all mankind, of all those who love me, of those who cry to me, of those who seek me and of those who have confidence in me. Here I will hear their weeping, their sorrow, and will remedy and alleviate all their multiple sufferings, necessities and misfortunes.

After Juan Diego received his mission, he asked the lady for her name. She responded in his native language of Nahuatl, “Tlecuatlecupe,” which means “the one who crushes the head of the serpent.” When pronounced correctly, Tlecuatlecupe sounds like Guadalupe, which is the Spanish name for a nearby city with a prominent Marian Shrine, and the name that Juan Diego may well have used when he approached his local bishop with Our Lady’s request.

Although he was a just and compassionate man, Bishop Zumarraga was, understandably doubtful. He sent Juan Diego away, stating that he needed to reflect further on the matter. Juan Diego returned to Mary, who in turn sent him back to the Bishop. So, Juan Diego ran this little relay a few times between Our Blessed Mother and the Bishop. On one occasion, he sought to avoid Tepeyac Hill altogether, his heart heavy with shame for not having yet achieved his mission, and also out of concern for his sick uncle, whom he was caring for at the time. Mary appeared to him, saying:

Hear and let it penetrate into your heart, my dear little son: let nothing discourage you, let nothing depress you. Let nothing alter your heart or your countenance. Also, do not fear any illness or vexation, anxiety or pain. Am I not here who am your mother? Are you not under my shadow and protection? Am I not your fountain of life? Are you not in the folds of my mantle, in the crossing of my arms? Is there anything else that you need?

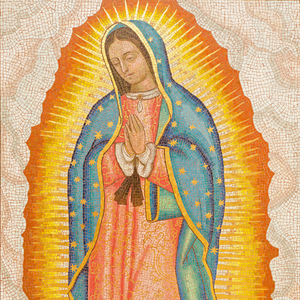

Mary reassured Juan Diego that his uncle would be restored to full health, and then sent him back to the Bishop with two signs. The first, several roses that were foreign to that barren, dry region, which he enfolded in his tilma, a poncho-like garment. When Juan Diego opened his tilma to spill out the flowers, the Bishop wept as he saw, there emblazoned on Juan Diego’s garment, the beautiful image of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

In the image, which hangs above the tabernacle in the Lady Chapel of Saint Thomas More, Mary appears as an indigenous woman. Her eyes are gazing downward, taking a position of humility. Her face exudes compassion. Her hands are poised in a manner of offering. Her waist is wrapped with a maternity band, signifying that she is pregnant, even close to giving birth, an indigenous sign that “someone is yet to come.” The turquoise color of her mantle, indicative of the indigenous supreme mother-father god, who was considered to be a source of unity for everything that exists. She is adorned with the rays of the sun, which is hidden by her figure, revealing that she is greater than the sun. She stands on the moon, indicating that she is greater than the indigenous god of night. The stars on her mantle, and the angel beneath her, symbolize for the indigenous people the end of one era, and the birth of a new one.

It is said that when Juan Diego appeared before the Bishop with the signs, the message, and the request from the Virgin of Guadalupe, torch runners were sent to deliver the good news of the miraculous apparition throughout the land. Harkening back to that moment, today up to 8,000 runners run The Guadalupan Torch Run, a relay by which a flame is brought overland from the Basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico City to Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. The run, which covers a distance of 3,000 miles over the course of seventy-two days, hails St. Juan Diego as a messenger of hope and healing for the indigenous people. It has also signified the hope of Dreamers, immigrants and migrants who make the thousands of miles trek seeking a new beginning in a new land. Most of all, the torch runners spread the message of hope embodied by Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Patroness of the Americas, who brought Christ to the New World.

Fr. Ryan Lerner, Chaplain

Fr. Ryan Lerner, Chaplain